The Monument/ Shadow Falls Park: The Hidden Abode of Recreation

The Mac-Groveland neighborhood is a predominantly white and affluent neighborhood presenting a liberal character. It is notable for containing two of the twin cities’ top private universities, Macalester, and St. Thomas, both established in the late 1800’s. This has given some parts of the neighborhood a distinctly “old money” air. However, the focus of this examination is the nearby Shadow Falls Park, as well as The Monument. SFP was an indigenous holy site of the Ojibwe before they were forced from their lands by white colonizers. The Monument was established by the Daughters of the American Revolution to commemorate those who died during WW1. We argue that the park perpetuates racist and classist segregation due to its inaccessible location and lack of public resources, despite, or perhaps because of, the fact that it has often acted as a safe space for those within the neighborhood.

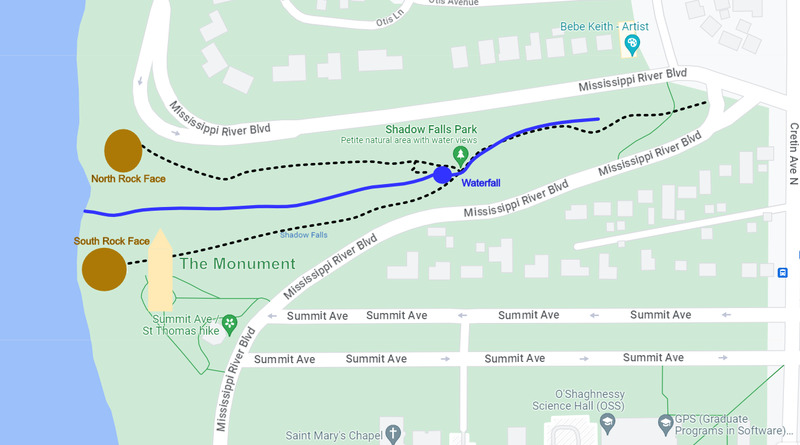

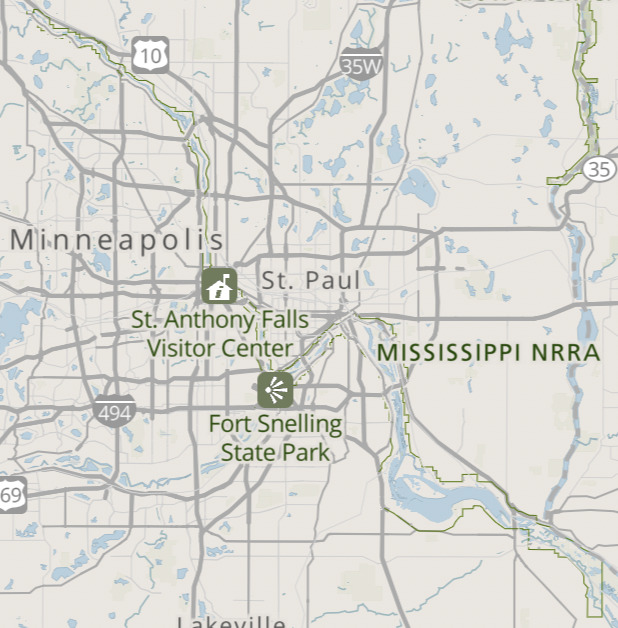

What we refer to as The Monument/ Shadow Falls Park is just a piece of a larger park called the Mississippi Gorge Regional Park, which runs from the Northern Pacific Bridge No. 9 to the outskirts of Minnehaha regional park. This is in turn part of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, which spans 72 miles of the Mississippi River. The MNRRA was established by the National Park Service as partnership park in 1988, while the MGRP was established by the United States Congress in 1998.

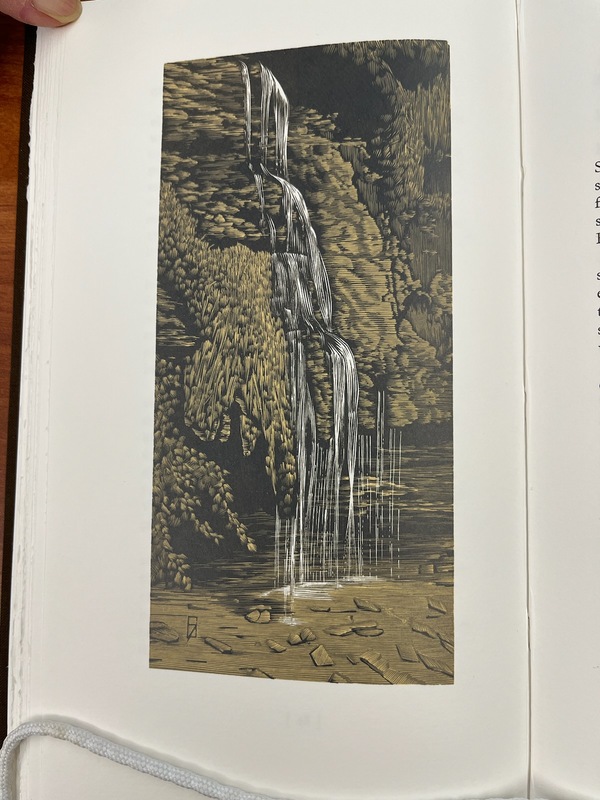

Shadow Falls was at one point a holy site for the indigenous Objibwe people of the area before European colonization, from European colonization and the forced displacement of indigenous people. The people who once considered this site as a holy site are largely absent today due to the overwhelmingly white and upper-class nature of the neighborhood. The history of this site as religiously important has also been largely forgotten, with no sign or monument to its significance. However, in that same space, an obelisk was erected to a world war one, further hiding the original importance of this space

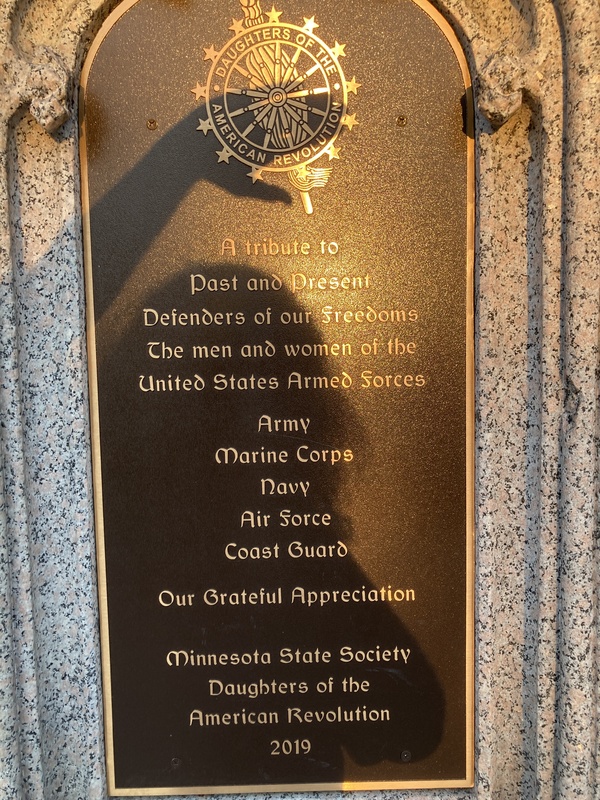

The Monument sits in roughly the center of the park area, but due to obscuring tree lines, it can really only be seen by driving directly down Summit Avenue, or by looking at it from the direct opposite river bank. The Monument itself is a looming gray granite pillar topped with an ornate, almost celtic, cross. Its base is octagonal, with rounded trapezoids of red brick outlined with roughly 8 inch wide granite slabs. Four granite benches surround The Monument, with two bushes on each side of every bench, which seem to have been planted at some point during the 2010’s. There are two ramps and two staircases which lead up to The Monument which correlate to the front, back, and sides of the cross atop the pillar. Two of the most notable parts of this monument, however, are the black and gold plaques which adorn the Summit Avenue and Mississippi River facing sides of The Monument.

The Summit Avenue facing plaque reads, “In memory of the men and women of Saint Paul and Ramsey County who sacrificed their lives in the World War. Greater love hath no man than this. Erected by Saint Paul Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution A.D. 1922." While the Mississippi River facing plaque reads, “A tribute to Past and Present Defenders of our Freedoms The men and women of the United States Armed Forces Army Marine Corps Navy Air Force Coast Guard Our Grateful Appreciation Minnesota State Society Daughters of the American Revolution 2019”.

People’s interactions with, and knowledge of, The Monument has seemed limited in our observations. Most people sit at the benches surrounding it and seem to ignore The Monument itself. At most, people would take a picture of/with it, or casually read the plaques. Few seemed to know its purpose beforehand, and in its google reviews, only 5 of the 183 reviews mention World War One, with one even claiming that it’s a monument commemorating World War Two. So if no one seems to care or know about the monument’s purpose, then why is it there in the first place?

There is a significant amount of strange historical circumstances surrounding The Monument, which I will get into now. One of the most glaring oddities is its name. Why, in more than 100 years has no one come up with a better name for it than “The Monument”, as if it were the monument to end all monuments (although honestly, there is irony in that). On the Historical Marker Database, it's referred to as the “Saint Paul and Ramsey County WWI Memorial”, which is a much more fitting name, however, this is a user created page that was only submitted originally in 2021. Another strange thing about this, is that the monument doesn’t seem to show up on the list of sites included within the MNRRA. Additionally, while The Monument has existed in this spot since 1922, this area would not be registered as a park until 1998, when the United States Congress deemed it to be one.

Another oddity is the fact that the monument exists at all in the first place. First of all, why does this monument exist in this part of the city? We have no concrete answer thus far, other than to perhaps raise property rates, reestablish white western european supremacy, or simply because it's a pretty spot. We’ll be getting back to that second point a little bit later. As for why they’re commemorating those lost in WW1 with this monument, we’re unsure. Firstly, the monument was completed four years after the end of the war, which we guess isn’t completely unusual, as spot finding and production may have taken a while to complete. But looking at Minnesota's actual casualties during WW1 also provides some confusion as to this monument’s existence.

According to MNopedia, during WW1, Minnesota sent 118,500 residents into the armed services, although only 57,400 went overseas to France, and of that, only one regiment, the 151st field artillery (also known as the Gopher Gunners) actually saw combat. In truth, only 2,133 Minnesotans died in the armed services during the war, and 60% of those were caused by the flu. These deaths make up about 2% of the U.S.’s total military casualties of 116,516 people. Additionally, the U.S. had the fewest casualties of both the Central and Allied powers. While the Gopher Gunners were celebrated as heroes upon their return, it’s strange that this seemingly obscure monument was created for what was, relatively speaking, such a small lot of casualties. Although, interestingly, that number of casualties is fairly similar to the number of people killed during the September 11th attacks, which was 2,977 people. Examining the builders of this monument may give us more context for its existence.

As stated before, it was built by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1922. The DAR are a lineage based service organization focused on patriotic education, genealogy, historical preservation, and some community service. Essentially, they’re ethno-nationalists pretending to be a service organization. They have attempted to alter school textbooks to fit their dogma, only allow members who can trace their family lineage back to the American Revolution, and had made efforts to exclude black people from the organization up until the 1980’s. In the context of 1922, when anti-german-immigrant sentiments were still very much at large in Saint Paul (Members of the german community in St. Paul, the largest ethnic minority group in the area at the time, were forced to register as “alien enemies” and had to carry their registration card with them at all times), this WW1 monument could have been a way to subtly entrench further anti-immigrant sentiment. This doesn’t seem too far-fetched in my mind, due to the DAR’s ethno-nationalist character.

With this context in mind, its renovation in 2019 may begin to make more sense. At the time, the U.S. was in the process of concluding an intervention campaign (see: neoliberalist colonial war) in Libya. Interestingly, this also coincided with a wave of ethno-nationalist sentiment in the U.S., this time against Arabs in general. It seems then, that this monument may not exist to commemorate the dead, or “honor the troops” (although that too is a loaded militarist/imperialist sentiment), but rather, it seems that this monument exists to quietly uphold white, western, masculine, christian supremacy. A dogma that seems to be the backbone of much of this gentrified neighborhood, steeped in traditions of western academia, and relying on the simultaneously exploited and excluded labor of BIPOC (and also poor white) communities to operate.

The monument park space is not accessible. The only space in the park that is ADA accessible is the area around the monument itself, which as we discuss is a less visited space, especially for younger people, who more often go past the monument and down to the rock face. The walk down from the paved area and lookout point is very steep, and can be made even more difficult by mud, snow, and other conditions. Shadow falls itself is slightly more accessible as there is a less steep path, but it is still certainly not accessible. This lack of accessibility keeps the most sought out parts of the park, making it exclusive for mostly young and physically able folks. Another way that the park lacks accessibility is in who is able to use this space. While nominally the park is public and open to anyone there are several ways in which it is restricted to particularly wealthy and white people. The makeup of Mac-Groveland means that most people who visit are either older white folks, sometimes with family, and college students, who also have a degree of privilege. The park is not easily accessible via public transit, as the 63 bus is the only public transport near the park, and it is still not close to the park itself. There is also only a very small parking lot further limiting access to primarily those living in the neighborhood, who are again primarily white and wealthy. The park is a valuable resource for everyone, and it is unfortunate that there are so many impediments to accessing this park, that further perpetuates social inequalities.

“Going down to the river is not accessible. And trying to get down to the waterfall to the quarry, like towards water or even just to go and look out over the, the river at the bridge is really difficult. And I've had friends who have mobility and chronic pain issues who've struggled, going down and getting back up there. And I mean, even I just as a person that is kind of doesn't work out a lot. *laughs* Like, when I come back up, I'm definitely heavy breathing, and it takes me a second. And then I have to walk all the way back. So it would be nice if there is some sort of ramp or accessible way to get to the water itself and acknowledging that like, that's what people come there for. No one's coming to look at the giant dick, *laughs* people are coming to like look at the waterfall. And look at the river.” - Jamie, a white college student from the area

One of Joseph’s interviewees contributed their thoughts about the safety of parks in the excerpt to the left:

As we can see, her gendered and racialized position within this society causes a sense of anxiety that, while lessened within the parks themselves, may discourage her from taking the transportation necessary to reach them. Therefore, by sequestering the park, and making the paths to reach it exclusive and hazardous, cities are able to present a space as having an open, public, and safe character while discreetly excluding marginalized groups from it via structural intimidation.

Not only is the park inaccessible in a material sense, but also in a social sense. The forms of social interaction present at the river are quite reflective of the nature of the community. While the river functions as a space of refuge for people trying to get away from the built-up city environment that Saint Paul offers, it still has an air of exclusivity to it. Unlike other parks that some of our group members have observed, ones which have better community amenities for the people in the area such as bathrooms, rec centers, and playgrounds, this park features a much lower rate of interaction between different social groups. This lack of interaction likely lends itself to the way in which the park functions, as it is a smaller space to stop on a broader bike trail heading across the Twin Cities. Its scenic view also functions as a sort of photo-op, but there is not much else to do at the park aside from this. For this reason, we see people doing their own thing quite often. In one observation, we see the ways in which these individualized activities can still play into broader dynamics in subtle ways: “I realize that there is a white man situated behind me playing guitar on the bench that I had been on at the start of my observations. A woman has come by the river to gaze at the view. She briefly turns around and stares at him in confusion”. The seemingly odd nature of a man playing guitar alone in the park in a central location becomes more apparent as we notice the ways in which a gendered lens can be applied to this. The man is playing loudly and in the vicinity of the woman, and the woman notices him and is confused by his presence. Racial grammar is present in this interaction as well as gender, as the message that the presence of this white man playing guitar speaks to how there is a degree of entitlement that comes with white people and men in Mac-Groveland. Because the area is designed around a white and affluent base, one which includes both older wealthy people or young college students, this white man is able to play guitar here without having to worry about potential harassment or violence. This contrasts heavily with other sorts of interactions present in the area. Oftentimes, the baseline is older couples coming to look at the view in pairs or alone, staying for a minute, and then leaving. However, some occasions present a more nuanced perspective: “...a Latine man emerges from the cliff with a backpack, seemingly talking on a phone. His appearance is somewhat unkempt, and he holds a bottle in his hand as he stumbles in circles around the area overlooking the cliff. A few white people walk by or look at the view while he is there, and largely ignore him”. This quote shows the ways in which people ignore those who are of different races and classes in the area in order to preserve the grammar of the area. This ignorance signals an important means of exclusion, and also makes the life of this person even more difficult, as they are not being provided with the resources they deserve. This social contract even extends into one-on-one personal interactions with white people, which speaks to the way in which this grammar is practiced in these circles, and then reproduced against others: “The two men from earlier are now in a more contemplative state, as they are quietly staring at the view. They laugh, and then the one on the right begins a phone conversation with his friend(?) right there…Throughout this conversation his friend remains seated next to him”. The degree to which the affluence and whiteness of the area makes social aversion a norm is evidenced here, and speaks to the broader disconnect present in the park.

To explore how the park is used as a hidden den for the afluent's misdemeanors, we have included an observation except detaling the abuses suffered by an innocent man on the bus ride to the park, contrasted by an observation of some park goers themselves.

"The bus arrived around 4:57, and the following event would play out before I exited the bus at 5:03. The bus was mildly dirty and sticky, as is fairly usual with our current public transportation systems. However, both the card swipe and the fare collector were covered in plastic bags, despite still being operational, which was unusual. It should also be noted that the driver had his clear plastic divider in position between him and the rest of the bus. I settled down in a seat opposite the driver’s side at the front of the bus, as I would be exiting soon, and the bus was fairly sparsely populated.

During the bus ride over, the white male bus driver (probably in his mid 30’s dressed in black pants, shoes, metro branded fleece jacket, neck gaiter, and beanie) pulls the bus over at a stop despite no one pulling the cord, and no one waiting at the stop. He then proceeds to yell back into the bus saying, “You there smoking, you know who you are, you need to get off bus right now!” Well, we all started looking around at each other to try to figure out who he was talking about, (at the time, I think the passengers were me, a female asian college student, a latino guy of about mid 20’s to early 30’s in a gray baseball cap, and a black guy of about the same age in some sort of a U.S. armed forces beanie and a black fleece jacket with a black and white back back. I was sitting between the black guy and the bus driver at an angle, the asian girl was sitting a few seats to my left, and the latino guy was sitting a couple seats behind the girl on the raised section of the bus. I think he then repeated, “you know who you are” and then angled a mirror at the black guy, and then may have said something along the lines of “yeah, you”. He then says something along the lines of “I saw you smoking from a little white straw” the black guy then raises the Motz juice box he was drinking from above the small plastic divider between the accessible seating and the rest of the bus and states to the bus driver that he was drinking juice. I also quietly and confusedly say that he’s drinking juice, as I was a bit shocked to suddenly be in this situation. I said something along the lines of, “Yeah, that’s juice.” The bus driver then tries to hurriedly shout back a short apology, but the black guy doesn’t relent and calls him out for the profiling, he also mentions that he’s suicidal, that this ruined his day, and that a cop had stopped him at a store earlier that day (he didn’t necessarily say that in that order) by this time, we had reached my stop, so I pulled the yellow cord and quietly got off while the bus continued onward.

While the juice box could have theoretically been confused for a methamphetamine bong from the driver’s angle, which also sometimes uses a small white straw, that apparatus would have produced a clearly visible smoke that the juice box couldn’t have. Also it would have been difficult to operate on a moving bus. More importantly, I have never seen a driver make that hard of a call on something they were so wrong about before, and as the black guy pointed out, this probably happened because he was black, and got profiled. Sort of like the bias test that asks people to state whether a held object is a tool or a weapon, and white respondents had a tendency to falsely identify tools as weapons in the hands of black examples more often than with white examples. This provides evidence on how black folks in the U.S. are seemingly in a constant war behind enemy lines, forced to live despite the constant attacks and slights. Additionally, even if he was doing drugs, which he wasn’t, throwing folks out because of it only reinforces the stigmatization and pain that may have driven a person to do drugs in the first place. And trying to pin crimes on people who never committed them makes them feel societally harassed and criminalized. It's a war upon, and criminalization of, black bodies and minds, or more generally, upon black people.

...

From 5:37 to 5:54, I listened to a few groups of young folks conversations down on the cliff. The first group seemed to be three white male college students, one sitting in a folding chair, smoking weed and talking about local parties, doing shrooms and more weed, and watching horror movies. Soon, they would be joined by two more college guys, one possibly white, one possibly black, judging off of dialects. One of them brought another folding chair. From listening to them, it sounds like one of them went on a music tour at some point. One of the parties they talked about included a bonfire and a mini ramp for skating. It seems that this group is made of stoner-skater-musicians. Their smoke generates a lot of sickly sweet weed smell down on the cliff. They talk about how nice the weather has been recently. They also discussed the LA and general east coast music scene. Apparently, one of them has a rich friend out west that throws big music producer parties in the Joshua Tree National Park."

As we can clearly see here, while outside of the park, innocents get profiled and harrassed, while the often afluent park goers are able to commit misdemeanors unmolested. (presuming that these students were below the legal smoking age.) This societal structure were crimes comitted in afluent communities often go unreported due to their occurence in exclusive abodes feeds into an othering of criminality. While crime occurs in all classes, due to the over monitoring of pooer classes, and the under monitoring of rich classes, a dichotomy is formed where the poor become associeted with crime and vice, while the rich create an assocation with justice and purity.